Screen readers help blind and visually impaired users access digital content by converting text into speech or braille. However, navigating multilingual websites presents serious challenges for these users. Key issues include:

- Language Switching Problems: Without proper language tags, screen readers mispronounce text, making it incomprehensible.

- Metadata Errors: Incorrect or outdated coding methods (e.g.,

xml:lang) lead to failures in language recognition. - Script and Pronunciation Issues: Misidentified languages result in garbled speech and braille output.

- Inconsistent Support: Screen readers like NVDA, JAWS, and VoiceOver handle regional language variants differently.

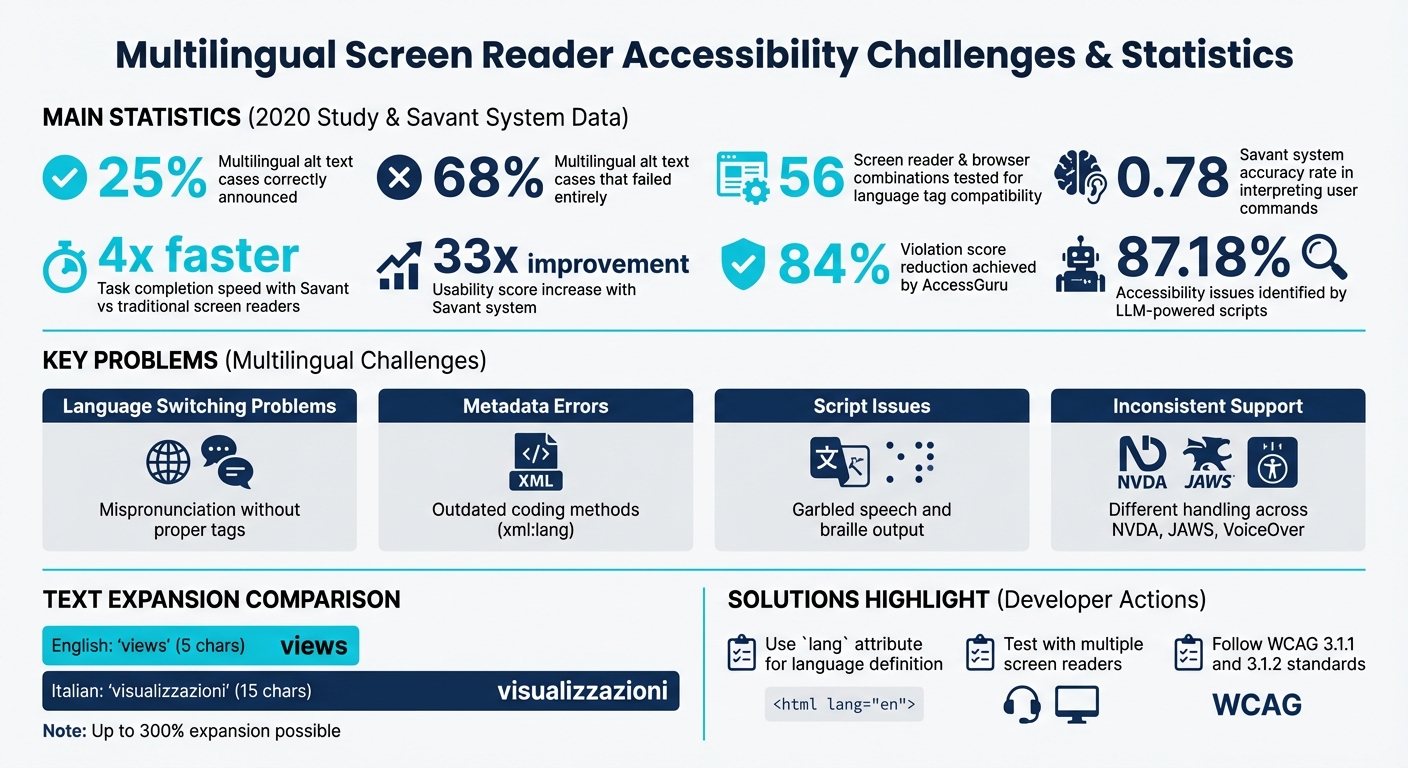

A 2020 study showed that only 25% of multilingual alt text cases were correctly announced, while 68% failed entirely. Recent tools like Savant and AccessGuru aim to improve usability by leveraging AI for better language detection and accessibility fixes. Developers can enhance multilingual accessibility by:

- Using the

langattribute to define languages. - Testing websites with screen readers to ensure proper functionality.

- Following WCAG standards for language tagging.

These steps can help reduce barriers and improve access for screen reader users on multilingual sites.

Multilingual Screen Reader Accessibility Statistics and Key Challenges

How To Setup Jaws To Autodetect Language #assistivetechnology #screenreader

sbb-itb-94eacf4

Technical Problems with Screen Readers on Multilingual Sites

Screen readers face significant challenges when dealing with multilingual content. These difficulties arise from two main areas: how language information is embedded in web pages and how assistive technologies handle different writing systems. Together, these issues create real barriers for users trying to navigate multilingual websites.

Language Tags and Metadata Issues

When websites fail to include correct language tags, screen readers default to their primary language (often English), leading to mispronunciations. As WCAG documentation points out:

"Without this [programmatic identification], foreign words or phrases would be mispronounced, making the content difficult or impossible to understand. Imagine a screen reader trying to pronounce a French phrase using English phonetic rules – it would sound like gibberish".

Some developers rely on outdated coding methods like xml:lang, which modern browsers largely ignore except for the root element. Testing across 56 screen reader and browser combinations revealed that using xml:lang instead of the standard HTML lang attribute resulted in widespread failures. For instance, Chromium 88 and newer versions completely disregard xml:lang on all elements except the root html element.

Regional language variants add another layer of complexity. For example, NVDA 2025.3 correctly pronounced content marked as lang="de" (German) but reverted to English pronunciation for lang="de-AT" (Austrian German) unless the corresponding language pack was installed. On the other hand, JAWS 2025 and VoiceOver on macOS handled Austrian German tags without issue. These inconsistencies highlight the ongoing struggles screen readers face with multilingual content.

But the challenges don’t stop with metadata - different scripts bring additional hurdles.

Script and Character Set Problems

When language identification fails, screen readers resort to default pronunciations, often resulting in garbled output. For instance, the French word "voiture" pronounced by an English synthesizer sounds like "voyture", which is far from correct.

This issue isn’t limited to speech synthesis. Braille output is also affected. If a language is misidentified, Braille translation software uses incorrect tables, leading to errors in accented characters and Grade 2 Braille contractions. For users relying on refreshable Braille displays, this makes reading content accurately nearly impossible.

Text length variations across languages further complicate things. A short English word like "views" (5 characters) becomes "visualizzazioni" (15 characters) in Italian, disrupting layouts. On the flip side, Arabic translations can produce much shorter strings, such as "Done" becoming "تم", which creates tiny touch targets that are hard for users with motor disabilities to interact with.

Right-to-left (RTL) scripts like Arabic and Hebrew introduce directional conflicts, disrupting visual hierarchy and navigation for users relying on screen magnifiers. Without proper handling of text direction, interfaces become confusing and harder to use. Moreover, some languages, like Latin or Haryanvi, lack pronunciation support in major screen readers, rendering language tags ineffective no matter how accurately they’re implemented.

Recent Studies and Proposed Solutions

The challenges faced by multilingual screen readers have prompted researchers to explore new solutions. Recent studies highlight how natural language interfaces and AI tools can significantly improve accessibility for blind and visually impaired users.

Savant Study on Usability Improvements

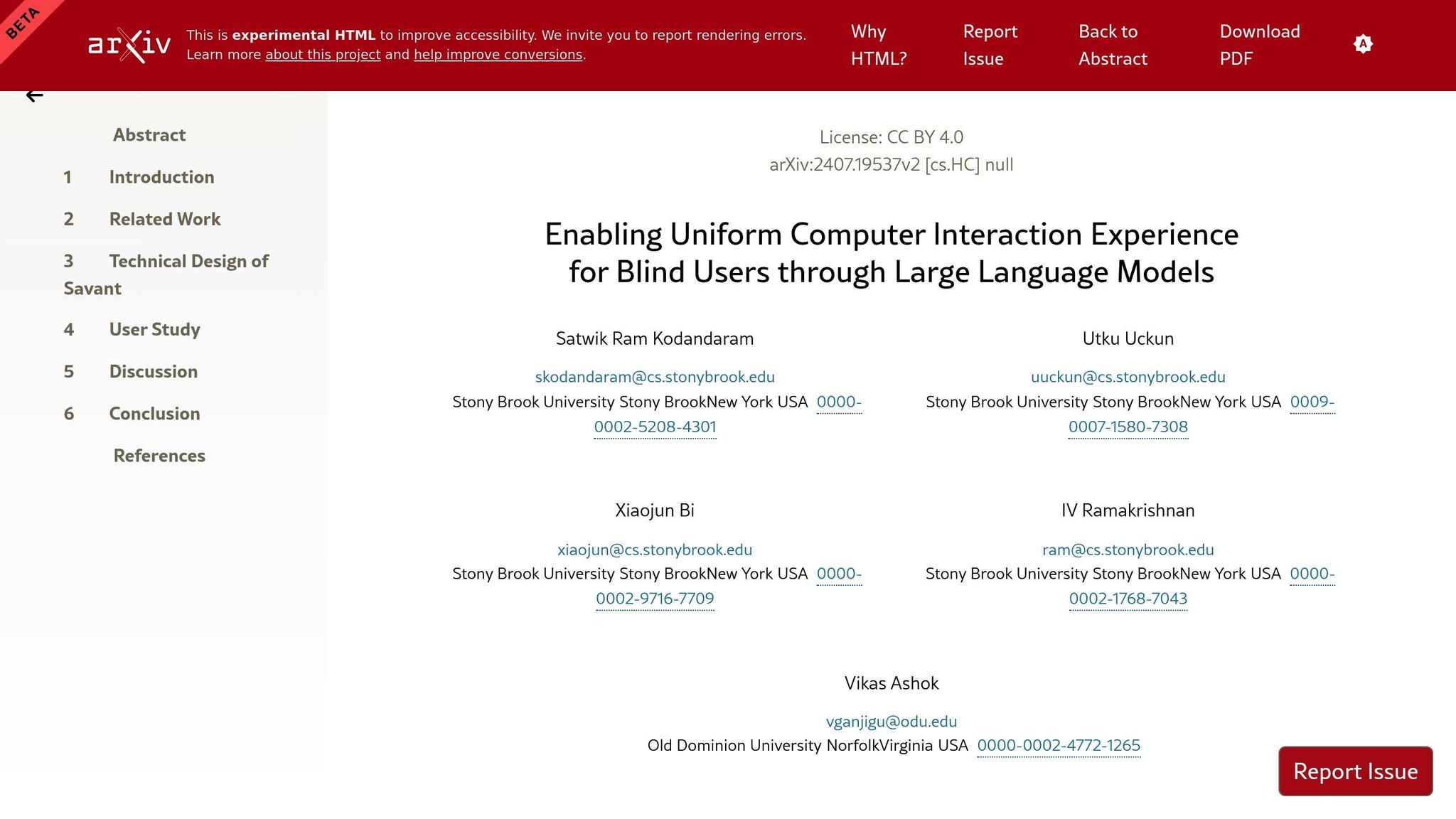

A collaboration between researchers at Stony Brook University and Old Dominion University led to the development of Savant, a system powered by large language models (LLMs). Savant allows blind users to control applications using simple spoken commands. For instance, instead of navigating menus in Microsoft Word, users can say, "set the margin to narrow", and the system automatically executes the corresponding commands (e.g., Layout Tab → Margins → Narrow).

In a study involving 11 blind participants across five applications (Excel, Gmail, File Explorer, Word, and Zoom), Savant demonstrated impressive results:

- Participants completed tasks nearly four times faster than with traditional screen readers.

- Usability scores improved by a factor of 33.

- Task workload scores dropped by the same margin.

"Savant... allows blind screen reader users to operate any application interface using natural language." - Satwik Ram Kodandaram et al., Stony Brook University

With an accuracy rate of 0.78 in interpreting and automating user commands, Savant showcases the potential of LLMs to simplify complex interactions and bridge the gap between user intent and software functionality.

AI and Large Language Models for Accessibility

Beyond command execution, AI tools are also tackling content accessibility. Researchers at the University of Stuttgart developed AccessGuru, a system designed to identify and correct semantic accessibility issues. For example, AccessGuru can spot when an image's alt text exists but is unhelpful (e.g., "image") and replace it with more meaningful descriptions.

When tested on 3,500 real-world accessibility violations, AccessGuru achieved an 84% reduction in violation scores, far surpassing earlier tools that managed only a 50% improvement. Another tool, SmartCaption AI, enhances image descriptions by summarizing the surrounding webpage content, ensuring metadata stays relevant even in multilingual contexts.

However, challenges persist. A study by Antonia Karamolegkou and colleagues evaluated twelve Multimodal Large Language Models and found areas needing improvement, particularly in cultural sensitivity and multilingual support:

"Our findings reveal challenges in contextual accuracy, cultural sensitivity, and scene comprehension, particularly for individuals who may rely solely on them for visual interpretation." - Antonia Karamolegkou et al., Association for Computational Linguistics

Despite these issues, LLM-based tools have shown remarkable promise. Scripts powered by these models successfully identified 87.18% of accessibility issues that traditional automated tools often miss. Together, these advancements are shaping a more inclusive future for multilingual accessibility.

WCAG Standards and Implementation Methods

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) provide a structured approach to ensuring multilingual websites are accessible, especially for screen reader users. Two specific success criteria stand out for multilingual accessibility:

- Success Criterion 3.1.1 (Language of Page): This requires developers to define the default language of a web page using the

langattribute in the<html>tag. For instance,<html lang="en">specifies English as the default language. - Success Criterion 3.1.2 (Language of Parts): This criterion mandates marking sections of text in a different language by applying the

langattribute to the smallest container of the foreign content, such as a<span>or<div>.

Screen readers depend on these language tags to load the correct pronunciation rules and voices. Without them, screen readers might default to the primary language's pronunciation, leading to errors. These guidelines bridge the gap between theoretical standards and practical implementation.

When applying language tags, use two-character ISO 639-1 codes (e.g., en for English, es for Spanish, fr for French) since most screen readers don't fully support three-character codes. Assign the lang attribute to the smallest possible element containing the foreign text, such as a <span> for inline phrases or a <div> for larger sections. However, some exceptions apply, such as for proper names, technical terms, or commonly used foreign phrases like "rendezvous."

Examples of Multilingual Accessibility in Practice

Platforms like Moodle demonstrate how WCAG standards can be effectively implemented. By consistently using language tags across course content, they ensure seamless transitions for screen readers. For example, if an English lesson includes a Spanish quote, wrapping the Spanish text in <span lang="es"> allows the screen reader to switch to Spanish pronunciation automatically.

Using Accessibility Audits to Improve Sites

Accessibility audits are essential for ensuring compliance with WCAG standards on multilingual websites. These audits focus on verifying the correct use of language codes and ensuring all content changes are properly marked.

Start by inspecting the <html> element with developer tools to confirm the primary language is set. Next, manually review the site to identify sections of text in different languages, wrapping them in elements with the appropriate lang attribute. For links leading to pages in another language, apply the lang attribute directly to the <a> tag, such as <a href="..." lang="es">Español</a>.

Testing with screen readers like NVDA or JAWS is a critical step to confirm that pronunciation switches occur as expected when encountering tagged content. Regular audits and updates help maintain and improve multilingual accessibility over time.

Conclusion

Screen readers often struggle with compatibility issues on multilingual websites. Problems like missing language tags and unpredictable language switching can make content inaccessible, especially for users who rely on screen readers in languages different from the developer's primary language. Technical challenges in language detection and voice synthesis further complicate accessibility.

To address these issues, developers should focus on a few key practices:

- Use the

langattribute on the<html>element to define the primary language of the page. - Wrap foreign text in properly tagged elements to ensure accurate language identification.

- Opt for visually hidden text instead of

aria-labelfor better language switching reliability. - Apply CSS techniques to handle text expansion and maintain layout consistency, as translated text (e.g., English to Italian) can expand by up to 300%.

Modern tools are making strides in simplifying multilingual accessibility. Many website builders now feature automated language tagging and templates designed to support WCAG standards. For developers looking for platforms that emphasize accessible multilingual development, resources like Top Website Builders provide a curated list of tools tailored for these needs.

FAQs

How can I tell if my site’s language switching works in NVDA, JAWS, and VoiceOver?

To ensure that your site’s language switching works seamlessly with screen readers like NVDA, JAWS, and VoiceOver, make sure the lang and xml:lang attributes are properly set. These attributes help screen readers recognize and switch languages correctly.

When testing, use screen readers that support language switching and ensure the necessary language packs are installed. For instance, NVDA can work with Windows OneCore voices if you’ve installed the appropriate language pack. Alternatively, it supports eSpeak voices without needing extra packs.

When should I use lang on a span vs the html tag?

To ensure assistive technologies can process content accurately, set the default language for the entire page using the lang attribute on the <html> tag. For example:

<html lang="en">

This helps screen readers and other tools interpret the content correctly.

If a specific part of your content is in a different language, apply the lang attribute to inline elements like <span>. For instance:

<p>This is an example sentence with a word in <span lang="fr">français</span>.</p>

This ensures screen readers pronounce and interpret the text in the appropriate language, improving accessibility for multilingual content.

What can I do if a screen reader doesn’t support a language or dialect I need?

If a screen reader doesn’t support your specific language or dialect, it’s crucial to declare the content’s language correctly using the lang attribute in your HTML code. This helps screen readers process the text more accurately. Some screen readers also allow users to switch languages manually, so it’s worth exploring those settings.

If support remains an issue, consider creating content in a language that the screen reader does support. Alternatively, collaborate with someone fluent in that language to test the content and offer feedback. Proper language tagging ensures better accessibility and usability for all users.